Releasing a movie is a surreal emotional rollercoaster that comes immediately after the years long psychological firefight you endured to actually make your film.

It’s also the reason you got into this business / art form — to birth your work into the world (although this will likely evolve and if you do it enough, your obsession with the process will become far more important than the results… truly, but that’s not why we are here today).

In this post you’ll learn about:

Handling the near constant rejection from festivals

Surviving bad reviews

Weathering the storm of bad offers

Dealing with family, friends, and ‘randos’ who saw your film

The long tail of a movie

I’ll be focusing primarily on WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING a film I directed, mostly because it helps me limit the length — but also because I’ll be inviting a few other directors to talk about the films we’ve produced/released together in the near future.

Ok. So what’s it take to bring a movie to audiences? A LOT. An unrelenting tsunami of rejection, followed by a brief tidal relief in which you catch your breath, before things get really heavy.

ON REJECTION

Most of you will be submitting your films to festivals as the first step in your plan to release your movie.

has recently written about all the things you should do FAR in advance of this to be prepared to submit to festivals, but you probably haven’t done those things yet. So let’s assume you’re doing what 95% of filmmakers do, and you just made the thing and are submitting blindly to festivals.First off, I personally believe if you are submitting to any of the top 25 festivals in the world, you have almost zero chance of being programmed if you haven’t personally connected with programmers, had someone connect with them on your behalf, become a part of those festival’s communities via labs, grants, etc., or are alumni. For real. Someone out there can contradict this, but I don’t know a single filmmaker who has just submitted to Sundance via some online form and gotten in. Not one.

I’ll let you in on a secret. When I submit to festivals, I always request a deadline or fee waiver. Not because I necessarily need it, but because I want contact with a real human at the festival — I want it on their radar. No one else will tell you this, but it works.

Anyways. Even with some tips, tricks, good festival tracking in place — you’re going to get rejected. Often many times, before landing a festival premiere. Especially if you’re big game hunting. This… doesn’t really mean anything. Film festivals are in the curation business, they are live events — they have to put on a show for their attendees, sponsors, etc.. This means your film needs to be of the quality associated with that festival, of course, but it also has to fit that year’s programming needs. You have a contemporary acid western set in NYC — great! But the programming team already fell in love with an East LA neo-spaghetti western. Any other year, your movie would have premiered, in competition. But this year, it doesn’t help create a diverse programming block. Sorry.

So don’t feel bad. At all. This doesn’t mean your movie sucks. NOT AT ALL. True story on a movie I produced — we submitted to a festival we LOVED. Thought our film was perfect for it. Heard the programmers were excited about it. And we got a lightning fast rejection. The director was shattered. Thought this was the beginning of the end for the film s/he had worked their entire life to make. And then another top tier festival heard about it from one of the programmers who had rejected it. The film premiered there, and won a major award. Far from being the beginning of the end, this launched the film into a phenomenal release.

I won’t lie though — when your films does get into a top festival. It feels AMAZING. When my narrative directorial debut, WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING, was selected for Tribeca, I about lost my mind. It was early 2021, deep pandemic times, and I was leaving a shoot in Phoenix, masked up on a mostly empty plane, row to myself, and seconds before takeoff I received an email from Matt Barone at Tribeca telling me he tried to call but my phone went to voicemail — they’d love to have the film premiere outside under a setting sun for the first Tribeca Festival since COVID started. I was so happy I was sure my plane would crash and I would die. And when these moments happen, mortal terror not withstanding, all the rejection is immediately worth it. Soon after we were selected for competition at Sitges, and a whole bunch of awesome genre festivals and OutFest after that.

Maybe you won’t get into a top festival at all though, and that’s ok! Plenty of films don’t premiere at top festivals and have great lives in release once an audience finds them. In fact, even a Sundance premiere doesn’t guarantee distribution anymore. This article is current as of today — 26 of the roughly 100 films that premiered at Sundance sold to distributors. 17 came with distribution already in place. Even adding those together is 43 films. Less than half of the movies at Sundance have found distribution 5 months after the festival.

https://www.indiewire.com/news/festivals/sundance-2025-movies-sold-1235086958/

Regardless of whether you premiere at a major festival, there’s still a LOT of work to be done to get your festival a release.

And in any case, you need reviews to build audience interest.

BAD REVIEWS

When WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING premiered, the reviews were pretty good. Better than I’d been expecting for a pretty wild horror movie with some extremely irreverent comedy splashed in. And for being something so bananas, it was also a deeply personal movie for me. Both because my life’s goal was to direct a movie. But also because thematically it was something that really came from my soul.

The initial good reviews were great. But I’d produced enough movies that I knew it wouldn’t last.

Here’s the thing. And I’ll get to this in a minute. You have to be somewhat immune to bad reviews, or you’ll lose your mind. Also, at a certain point, if you didn’t make the movie for yourself, I don’t believe you should have made it. And if you love it? Great. Let some people hate it. But no one. NO ONE. Wants their movie to be ROTTEN on Rotten Tomatoes. Yet, it happens. Frequently if you work in genre.

And sometimes it gets personal. Especially on Letterboxd — which I’ll share over traditional reviews because they are short and easy to screenshot. Here are a few of my ‘favorites’.

I remember reading one that said I should stop making movies. But can’t find it now.

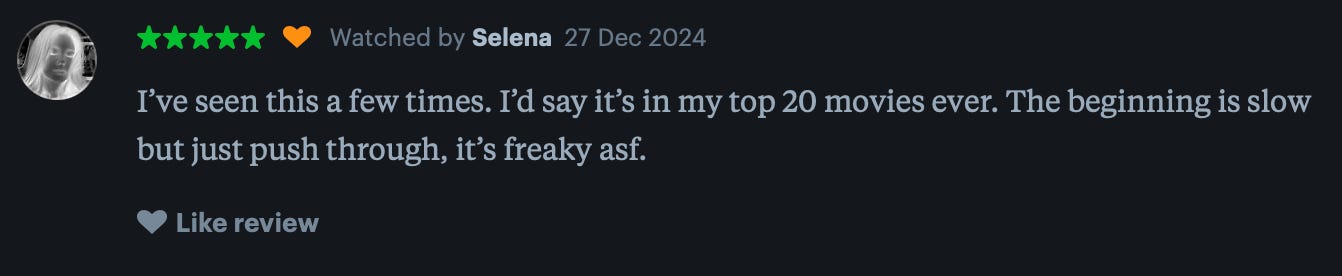

And then there are reviews like this:

It’s really cool to know you were a part of something that added value to people’s lives, if only for 90 minutes. I got into making films because they helped me through some rough times, and even if 95% of people HATE your movie, it might really be meaningful to the other 5%. And that’s something worth fighting for.

This kind of borderline cognitive dissonance — taking the bad reviews in stride, while embracing the good reviews, is critical if you are to manage your mental health while also publicly releasing any kind of art.

Literally I was told this was the worst movie someone had ever seen, and that it was someone’s favorite movie. Those are some wild opposites to hold in your head at the same time.

In the case of THE MILL, which I wrote about last week, the film stimulated the conversation I was hoping it would. Primarly on YouTube of all places. And largely on an AI summary of the film with over 1.2 million views… a film which featured an AI antagonist. Weird.

You can’t ever know how the public will respond to a film, but they will respond. So be prepared.

BAD OFFERS

I don’t care how great your film is, and how well it’s reviewed, you will get bad offers, and they will likely come in first. They will terrify you, and especially your investors, and the truth is in today’s market — you’re lucky (or at least told to be lucky) that you are getting these at all.

On WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING, we started getting offers before the festival premiere. And they were grim. $0 up front for many, and an amount of money that was frighteningly close to $0 from others. Then something happened. A good one came in. And then an even better offer. Finally, a truly great offer came in from IFC Midnight who ended up distributing the film in the US. We also got sales interest from a handful of international sales agencies (Verve was selling domestic), and landed with a brand new company called The Coven run by Priscilla Ross Smith and Kendall Anlian. While they hadn’t sold a film yet, we liked them. And they loved the movie. It was a good fit, and they ended up BLOWING UP a few years later by selling and then producing the TERRIFIER movies. They are now amongst my closest collaborators and we are working together on many projects. But selling WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING internationally was not easy. They faced a TON of rejection. This was a contained and bleak movie produced at a bleak time when we were all trapped inside. It also featured gay main characters, which can be tough for some territories. Again… rejection. Rejection. Rejection. Until there’s some acceptance. The Coven pushed HARD and eventually the film was distributed all over the world, including in territories that are considered tough for LGBTQ subject matter, such as Russia and MENA (Middle East North Africa).

BRACE YOURSELF for bad offers, and a lack of offers. It’s tough out there, but if you don’t take it personally (which is easier said than done when something is your personal vision) you’ll fight through the bad, and get to the good. Even if that means bringing it to market yourself. And of course you should all be creating your own audiences now anyway, to avoid this entire mess.

DEALING WITH PEOPLE IRL

Hearing critics and random naysayers alike bash your film online is one thing. Facing your friends, family, and random people at your significant others’ work who might not be into your kind of movie is a whole other ball of wax.

In the NY/LA indie film saturated worlds, people know the names of actors other than Tom Cruise. They know the names of directors, writers, producers, and film festivals. Where I live? No one has a clue. When I’m discussing my work and mention having films in Sundance, this means less than nothing. When they ask where they can see my film and I say “it will be in theaters in October” they say “Real theaters? Like around here?” When I say I make films, they say “oh, like commercials, yeah I met a guy who does that?” (I do that too, by the way). Or they’ll tell you about some other guy who lives nearby who makes ‘real’ movies — I promise they are not anymore real or unreal than yours.

Get used to this. No one ‘in the wild’ will take your indie films seriously — until they suddenly think one is a big deal because an actor in your film had a guest arc on some random network sitcom. There are like 10 people who introduce me to other randos as “this is Sean, he produced a movie with that girl from Ozark”, because I EP’ed THE ASSISTANT starring Julia Garner. And if you make horror movies, or anything remotely subversive or sexual in nature? Good god, man. Are you in for it. I swear to you my neighbor watched WE NEED TO DO SOMETHING and told me his wife cried and said she wasn’t sure I was a good influence to have around her kids. And these are people who like me!

The thing is, who cares? Do you care about the insurance products your pickleball partner sells unless you need to buy one? NO! Do you critique the curriculum your 3rd grade teacher neighbor put together? OF COURSE NOT!

Oh, and there’s a flip side. Other people will say, “Wow, you have such a cool job,” and you start to feel good for a moment, then the followup usually is, “have you met any celebrities?”. Make sure you have a good go-to story lined up for this, it will save you in more social situations than you can imagine.

Much like good reviews and scathing reviews, occasionally you’ll meet a genuine film buff and get to bro down. But it doesn’t happen often. So enjoy it when it does, and don’t care when it doesn’t.

THE LONG TAIL OF A MOVIE

This is a tricky one for me. And might come across as contradictory because I’m here writing about a movie I made 5 years ago. But I don’t love revisiting my old work.

There are some filmmakers who do. In my followup to this in which I interview several other filmmakers, I’ll talk to one filmmaker who will travel anywhere anytime for any screening of his films. Regardless of when he made them, or if he’s being compensated. And the thing that really gets me, is that he sits through the entirety of each screening. Opening credits through end crawl. He truly, truly loves it.

I’m of course happily committed to promoting my films, and to being extremely grateful for and respectful to anyone who wants to screen one. Or talk about it. Or anything. I’m proud of each and every one, and am thrilled to the point that it often feels like I’m dreaming that I was able to make them.

However, I do not enjoy watching my films really at all once they’ve premiered. I see only flaws. I’m also onto my next thing, excited about making and talking about whatever that might be. For better or worse, I live largely in the present and future.

Here’s something I think you’ll ALL relate to: you know that feeling of reading something you posted a few weeks back? And how you are such a better writer now and it all feels cringe and oh god why did you post it??!? Yeah… I get that feeling when it comes to movies. I immediately see 10 minutes that should have been cut, dozens of decisions I’d have made differently, whole scenes I’d have rewritten, reblocked, and re-edited. It’s tough.

No matter what, you will be talking about every movie you make for an extremely long time. Regardless of whether you like doing this — it’s a necessary part of engaging with people who have thoughts about your films, and also making sure the film has a good life out of respect for all the people who put so much into it — their time, talent, resources, and most importantly love.

Because of this, you need to be sure it’s about a subject matter you are comfortable living with for the rest of your life. That sounds extreme, but it’s not. I’ve passed on really cool opportunities because I’ve realized I didn’t want to be talking about (INSERT SUBJECT MATTER HERE) ten years down the road.

These were all things no one really prepared me for in the build up to releasing my first films, both as a producer and director. I hope you all can gain some insight from the things that have pained me, and also given me joy.

PEACE!

Sean

P.S. I know I said I’d be writing about current projects. That starts next week. Had to get this out first.

P.P.S. I haven’t been as engaged on this platform as I’d like to be over the past week. The aforementioned current projects have been eating up a lot of time. Some of you write so thoughtfully that it takes me a while to read and respond to your posts. But please know I’m LOVING what you’re all doing, and will get to it in due time. THANK YOU.

Thanks so much for these insights, Sean (especially the hot tip about reaching out for a fee waiver! GENIUS!). A short that I wrote and produced (based on an award-winning play I wrote and directed) “only” screened at two festivals last year. A younger me would have been devastated by the 40+ rejections we received along with those two yeses. The first festival was a cold submission, but the second came when our producers who attended met the owner of the Female Eye Film Festival in Toronto at the premiere. She loved our film and actually shuffled things around in the already programmed FEFF to squeeze us in. We got to have a hometown screening in Toronto and invite all our friends and family. It was an incredible evening and one none of us will ever forget. As I get older, I realize that’s why we do this crazy shit in this crazy industry! :)

Thank you, Sean. You are not alone. It may be dreaming but I cannot stop thinking we can change this.